Ian Wigginton

A few weeks ago The Hill Times published an Op-Ed by William Leiss an emeritus professor at Queen’s University, where his specialism was risk communication. I can’t reproduce the article which is behind a paywall but it can be found here https://www.hilltimes.com/story/2024/10/07/canadas-false-solution-for-used-nuclear-fuel-waste/436907/ by subscribers to the paper. Its headline was “Canada’s false ‘solution’ for used nuclear fuel waste” and it was subtitled “Potentially trucking waste to a deep geological repository could be a recipe for disaster”.

The central argument is captured in this quote “But trucks travelling 168 million kilometres are—quite obviously—going to be involved in a fair number of road accidents, some serious, across those four or more decades. In those cases, folks likely will be told, “Don’t worry, it may look awful, but you and your kids won’t be irradiated.””

The interesting thing for a risk communication specialist is that he conflates two entirely separate risks, the risk of a road traffic accident and the risk of a nuclear incident. He takes the almost statistical certainty of an RTA occurring and parlays it into the idea that nuclear incidents will occur with the same frequency. Note he never actually says it, just implies it, and as he is implying something that is not true that is a huge risk communication failure.

The co-chair of the CNS Environmental and Waste Management Division wrote a personal response and sent it to the Hill Times but at this time we have not seen it published. It’s a good piece and worth repeating here.

The Opinions within this Article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Canadian Nuclear Society

Prof. William Leiss’ opinion piece about the transportation of Spent Nuclear Fuel along the highways of Canada correctly observed that with the volume of vehicle movements, they could be involved in a Road Traffic Accident (RTA). Some people may have inferred from this that such an accident would give rise to a major nuclear incident as Prof Leiss did not make it clear that this does not necessarily follow. In fact, in all probability any RTA, even if it did occur, would likely just be a classic RTA and the sealed spent fuel storage container and transportation package designed such that there will be no release of radioactive materials will remain unaffected. The design and qualification of sealed spent fuel storage container and transportation package is such that releases for more severe and improbable accidents would be well under the regulated acceptable dose limit and safety objectives.

The reasons for this limited potential harm are fundamental with engineering being used to minimize risk of anything whatsoever happening.

The implication that there could be a significant radiological incident arises from the Simpsons created image of used nuclear fuel as a green goo that has caught the public’s imagination and is routinely used by anti-nuclear campaigners to mislead the public. This mythical green goo is obviously capable of leaking and flowing implying that used fuel may do the same. However, the reality is much more mundane as there is no liquid in the spent fuel, in the storage basket or container and no liquid in the transportation package, so nothing can flow.

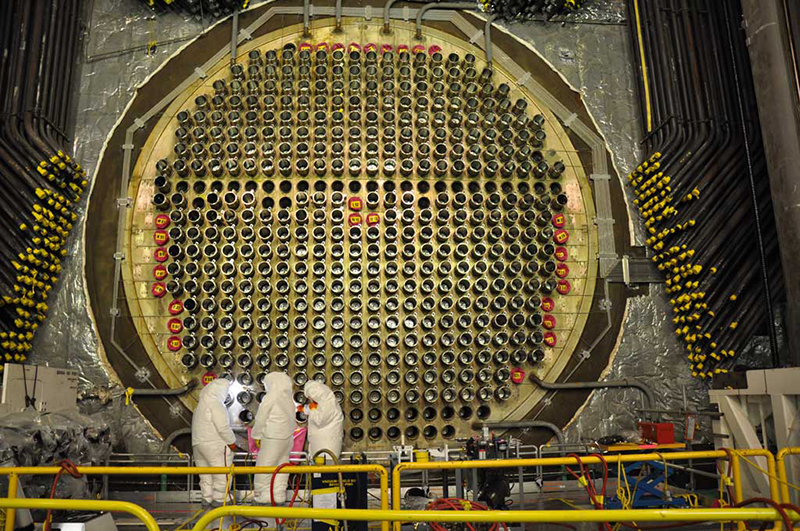

Here are the facts. Canadian nuclear fuel is made of pellets of dry Uranium Oxide, a ceramic. The plates in your kitchen cupboard are ceramic and similar in physical properties to these pellets. The pellets are contained in metal tubes welded together into bundles the size of a fireplace log. As a result of their time in a nuclear reactor some of the uranium has been transmuted into fission products and that gives rise to a tiny quantity of radioactive gas which is mostly held within the structure of the ceramic and will remain held in the tube unless it is punctured. There are no liquids.

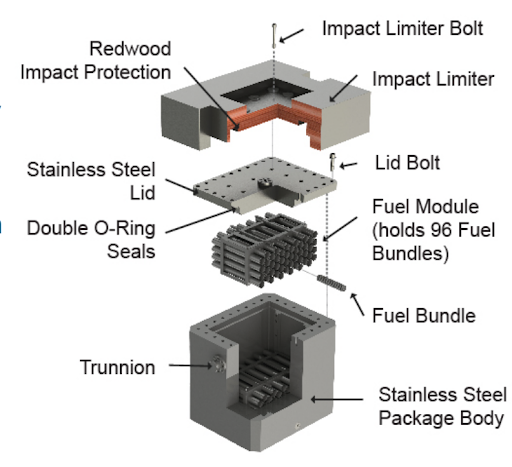

These bundles will be transported in containers that fulfill three functions:

- They keep the bundles in place and protect them from an impact so that the tubes are at no risk of puncturing.

- They provide shielding as radiation (not radioactive materials) will be being emitted by the bundles.

- They provide a secondary containment as they are sealed so that in the unlikely event the integrity of a tube is lost any gas that does escape will remain in the container.

The shielding requires a sufficient thickness of steel and other shielding material, and that thickness of steel gives considerable engineering margin for the other functions, notably keeping the bundles in place and preventing anything from puncturing them.

The containers are designed to retain their integrity in any possible accident that could occur during their movement and tests are undertaken to provide assurance in the design. Possible accidents that are considered include being smashed into by the largest fastest -moving vehicle that they could come into contact with, being punctured by any projectiles, being involved in fires arising from oil spills, and being immersed in water for a significant period of time, to name but a few.

Consideration is also given to multiple events such as being hit by an oil tanker which bursts into flame before the container tips over a bridge into a river.

The tests are to prove that in all these circumstances the seals remain effective. In all such circumstances the bundles are still expected to remain held in their structures within the thick shielding so that the primary containment remains intact, and nothing escapes the fuel tube itself.

The transport containers will be securely fastened onto specially designed trailers. These fasteners will be sufficiently robust to retain the container in any circumstance including tipping over.

The containers will be escorted, for security reasons, and shipments will not take place in adverse weather conditions out of respect for worker safety, so the risk of a conventional RTA will be minimized anyway.

Taking all of the factors above into consideration, whilst it would be naïve to expect that there would be absolutely no potential for RTAs, the strength in depth provided by the integrity of payload, container and transport would, and the fact that there is only a tiny quantity of mobile material anyway, means that the consequences of such an event occurring would be nowhere near as catastrophic as Prof. Leiss may inadvertently have led people to believe.

Popular Core Business Articles

- The important differences between Hazard, Danger, Risk and Fear when considering a Deep Geologic Repository for used nuclear fuel.

- Deep Geologic Repositories (DGRs)? Distressed purchase or Jewel in the Nuclear Crown

- An article by the Breakthrough Institute

- How do we quickly and succinctly explain why wind and solar are not cheap?

- The Titanic Fallacy

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.